Although not about one of the sites that form a focus of the Past in its Place project, this recent blog entry explores the material practices taking place at sites of pilgrimmage, particulary from the 19th century. It is reblogged here from Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath site.

Recently I visited St Winifred’s Well, a tourist attraction and Christian cult focus at Holywell, Flintshire. For further details see their website here.

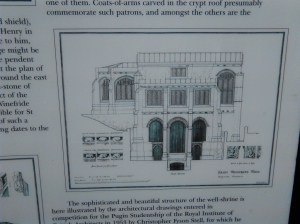

With twins in tow, I didn’t get a chance to walk around the museum, but I did get the opportunity to explore well chapel itself: the ‘Lourdes of Wales’. A focus of legend associated with the supposed 7th-century female saint. Wini lost her head to save her virginity from a rapist, and it miraculous was reattached. Headstrong Wini lived out her life a nun and her cult grew throughout the Middle Ages. The structure you can see is a phenomenal early 16th-century well-chapel with later additions during the 18th and 19th centuries.

As with all foci of veneration by pilgrims, there are various ephemeral material cultures that inhabit and augment this space, from candles to cards. There are also different forms of memorial.

Commemorating the Dead

The historic churchyard associated with and uphill from the chapel has now been cleared completely, but it is a strikingly steep space that reminded me of Coalbrookdale’s Quaker burial ground. Along its western edge there remain a collection of in situ and relocated memorials of 18th- and 19th-century date.

More recent memorials allowed in the chapel grounds take the form of our good old friend the memorial bench. These include a notable number to ladies named ‘Winifred’. Lining the route to, around and within, and from the well, these benches allow the dead to be remembered at, and presenced at, the holy well.

A further memorial or votive practice is placing potted plants and flowers around the statue of St Winifred in front of the well.

Commemorating Cures

The most prevalent historic form of memorial is the graffiti that adorns all surfaces, including notably the sites of the structure that face into the waters. The motives of inscribers are unclear: counter-souvenirs of the act of pilgrimage itself (i.e. marking the place been to rather than/or additional to bringing a memento back with the pilgrim), dedications of prayers to Saint Winifred for hoped-for cures, or commemorative statements celebrating cures received by pilgrims. There are forms of graffiti familiar from cathedrals where pilgrims have thronged around the crypts and shrines containing the remains of the saintly dead.

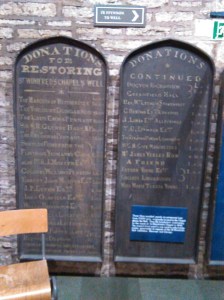

In the visitor exhibition there are wooden boards recording financial offerings to the chapel, as well as another form of discard; crutches left behind by cured pilgrims. Crutches were something I hadn’t encountered before as an assemblage of similar artefacts at a sacred site. They reminded me of the sinister display of artefacts in horrific piles at Auchwitz-Birkenau; the possessions – suitcases, shoes, cut hair etc – of those killed by the Nazi regime and serving as material testimony to this atrocity. Yet at St Winifred’s while the former owners are undoubtedly now dead, these artefacts commemorate cures and the lifting of suffering by saintly intercession.