From Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog.

From Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog.

Recently I had the opportunity, as part of the Past in its Place project, to visit Birmingham Cathedral and explore its memorials together with my doctoral student Ruth Nugent. We met their new and superbly helpful Heritage Manager, Jane McArdle, and explored the churchyard and inside the cathedral church itself.

In previous blogs, I have outlined some of the interests we have in cathedral commemoration over the long term here and here and here and here and also… here.

Only late in the project has it become clear that, despite the sensitivity of our project to comparisons between cathedrals and in embracing cathedrals as environments over the long term, our sample lacked comparative information about more recent cathedrals dedicated in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Hence Ruth and I visited Birmingham Cathedral. This church, originally an early 18th-century baroque church dedicated to St Philip (consecrated 1715) and only achieved cathedral status in 1905.

First Impressions Inside

Visiting Birmingham Cathedral was fascinating on many levels; such a contrast to experience an 18th-century church subject to renovations and expansion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, operating as a cathedral. Birmingham stands in contrast to the heavily reworked medieval buildings that have been the principal focus of our research elsewhere. The church operates on a smaller scale. It has the light, airy, optimistic and vibrant atmosphere of its baroque origins, plus it has many memorials of 18th and 19th century design and date. Indeed, the memorials felt more ‘at home’ in the light environs.

Of course by this I don’t mean that they are somehow more, ‘authentic’ or consistent in this space; many have been moved from other churches in the city, many have probably moved around within the church.

A key difference was that the 18th and 19th century memorials were well ordered and spaced out, not interpolated or sidelined by older memorials. A further point: memorials were fewer in number compared with larger medieval cathedral churches. A third point was the lack of ledger stones; only a few memorials were upon the floor surfaces and these were all 20th century. Hence, at Birmingham, the 18th and 19th-century dead are on the walls, the 20th-century dead have moved to the floors and fittings.

Professions and the Antique

Birmingham possesses a wonderful array of mural monuments, many high-quality examples of neo-classical draped urns and draped tombs. Also notable is the number that employ distinctive artefacts and symbols of professions – doctors, secretaries and so on – in their design.

Bishops

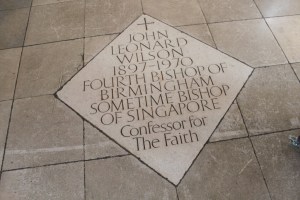

In such a modern cathedral, it is interesting how the bishops get commemorated, in diamond ledgers and one mural monument. Only one memorial was demonstrably and distinctive paired with a place of interment of cremated remains beneath the only 20th-century mural monument.

Wilson’s diamond ledger stone – a former FEPOW who endured capture and incarceration in Changi jail, having been Bishop of Singapore at the time of the British surrender to the Japanese.

The Military

Despite the pacifist status of the third bishop, and the long-term wartime suffering of the fourth, it is notable that the 20th-century memorials of bishops are paired with the ubiquitous dominance of military memorials.As with all cathedrals, the military dead are commemorated in many fashions.

There is a First World War memorial, regimental flags, ship’s bell and plaque (HMS Birmingham) but notably only a few to individual military personnel and none of the 19th-century grandiose memorials to the military that would have made their way in here had this been afforded cathedral status a century or two earlier in an older county city.

Indeed, military commemoration dominates Birmingham temporarily at the present. A number of mural monuments we couldn’t see because they have been temporarily obscured by the red drapes that define the cathedral as a place of mourning to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Great War. There is also a temporary shrine with poppies, sandbags and even a model carrier pigeon.

Conclusion

I am very glad that we followed up on Ruth’s suggestion of visiting Birmingham Cathedral and we are grateful to the cathedral’s staff for a warm welcome and support for our project. It was a worthwhile place to visit with many dimensions connected to the project’s research aims. Be warned though, Birmingham Cathedral lacks its own cafe, so one is forced to utilise Gregg’s, McDonald’s and various other fast-food outlets close by.

In commemorative terms, the mural monuments of the late 18th and 19th centuries are the majority. The military dominate the presence as well remember the Great War. Yet it is the humble memorials of the bishops that set this cathedral apart from the grandiose clerical monuments of many other cathedrals. The bishops’s memorials do not dominate in numbers given the youth of this cathedral church. Still, in spatial location upon floors and walls, particularly Wilson’s centrally placed ledger, they define the spirit and identity of this holy space at the heart of one of England’s greatest cities.