I have blogged about Project Eliseg on previous occasions, and the public talks I have presented about my work on the Pillar of Eliseg (e.g. Holt, Llangollen, Corwen and Keele). However, every visit to the monument itself is different: it changes with the weather, the seasons and with the activities of the farming regime of the field surrounding it. Equally important is the fact that each visit also varies depending on the company: their responses, ideas and questions.

This time, I was joining a fieldtrip run by Dr Adrian Maldonado – my replacement this academic year – with students on the MA Archaeology of Death and Memory. Adrian was superb in getting the students discussing the complex biography of the monument from its Bronze Age origins as a burial mound, through its early medieval reuse as the location for a stone cross with a memorial inscription and through the medieval and modern uses and reuses of the monument. We also discussed Project Eliseg’s excavations on the site from 2010-12. Afterwards we had an amazing hot pork and apple sauce bap at the Abbey Farm before exploring Valle Crucis.

The Pillar and its mound looked particularly fine in today’s sunshine (yes, sunshine, would you believe it!). More information can be found on the Project Eliseg website and our Youtube video blogs. Inspired by Adrian and his students, I thought this blog might be a useful point to outline, in material terms, some basic information about the Pillar’s complex biography evident on the surface and revealed through our 2010-12 excavations. In the spirit of a genealogy, rather than a biography, I begin with the present and move back into the past.

21st century – Archaeology, Reconstitution and Restrictions

There are plenty of traces of 21st-century activity on the site. Our excavations and the subsequent consolidation by Cadw have altered slightly the shape of the western side of the mound that had previously become worn by footfall.

The wooden-post fence-line around the base of the mound is a construction by Cadw following our first, 2010, season of excavation to guide visitors around to the east side of the monument where there is a small stile allowing access up to the monument. Sadly, upon observation and discussions with visitors, this isn’t visible and many visitors simply don’t approach the monument anymore. Meanwhile, those with disabilities have no effective access to the monument. It was particularly embarassing to learn that an eminent medieval archaeologist couldn’t access the monument in this account.

The wooden-post fence-line around the base of the mound is a construction by Cadw following our first, 2010, season of excavation to guide visitors around to the east side of the monument where there is a small stile allowing access up to the monument. Sadly, upon observation and discussions with visitors, this isn’t visible and many visitors simply don’t approach the monument anymore. Meanwhile, those with disabilities have no effective access to the monument. It was particularly embarassing to learn that an eminent medieval archaeologist couldn’t access the monument in this account.

20th century – Heritage and History

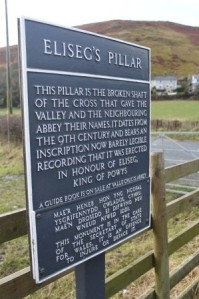

There is no modern heritage presentation of the site, which is one of the reasons why we got permission to dig in 2010-12, to inform subsequent heritage interpretation. Instead, one is left with the starkly antique signboard. I am not sure of its precise date and chronology, so I am happy to be corrected. What is interesting is that, while the sign is largely accurate, it is monolingual. The sign too has a biography however, since the sign below it is later and bilingual. Adrian and the students noted that its position prevents it being seen from the road, meaning that you have to have entered into the field first to read it. This prevents the danger of people stopping their cars in a perilous position to read the sign, but equally it restricts interest and notice from passers-by.

What features on the monument itself are 20th century? Visible before our fieldwork, but now hidden, are the octangonal concrete pillars that mark the edge of the scheduled area with ‘MOW’ on their tops. Meanwhile, the iron fence around the top of the monument mark its protection as an Ancient Monument. These are key material culture of heritage conservation. In addition to this, there are traces of the stone’s consolidation with iron pins and concrete, ensuring it stays in place. Other traces on the monument are not exclusively 20th-century, but are shared by the centuries following its construction – but the acid rain of the 19th and 20th centuries might have caused a large portion of the erosion.

19th century – Tourism and Trees

The trees that were planted on the mound have left subtle traces on the surface. Meanwhile, the foot-fall of the many tourists that visited the monument in the 19th and 20th centuries created a depression on the western side prior to our consolidation. A range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century artefacts recovered during excavation reveal the many people visiting the site. Moreover, during excavation it became apparent that the reason the cross-shaft and base sit on a visible drystone base within a saddle is because the original reconstitution of the monument in the 1780s was subject to erosion from visitors and livestock, taking away the soil that had been thrown up around its base and revealing the drystone base that I think was originally intended to be obscured from view.

18th century – Reconstitution and Rededication

The entire monument, as it appears today, is the product of Trevor Lloyd’s reconstruction. His re-dedication of the monument to himself (very modest of him) is revealed in the Latin inscription on the eastern side. The drystone base upon which he re-positioned the cross-base, and inset into it the cross-shaft fragment, are all his work. He may have done this to make the re-erected monument more visible from the summer lodge he constructed beside the fishponds next to the ruins of Valle Crucis Abbey.

17th century – Absent Presences

There are no exclusive and conclusive traces of seventeenth-century Pillar apart from absenses. The cross-head was presumably still in place when the cross fell down c. 1640 and the remaining reconstituted monument foregrounds its absense. The lack of the legible ninth-century Latin inscription is implied by faint traces, but the seventeenth century saw Edward Lhuwyd transcribing them, thus saving them for modern academic study as discussed in detail by Prof. Nancy Edwards.

The Middle Ages – Naming the Monument

What is particularly frustrating is lack of direct evidence for activity around the cross in the period between its ninth-century construction and the seventeenth century. There was not conclusive evidence of medieval activity from the excavations. Instead, evidence of the veneration held for the cross comes from the place-name itself – ‘the valley of the cross’ by which the Cistercian monastery was known. This is an example where lack of activity might indicate respect rather than neglect. We can imagine monks and travellers passing by the Pillar when its cross was still intact and using it as a station in processions or as a shrine, but no evidence has been left of this.

The Ninth-Century Cross

Only two fragments of the original cross-and-base survive and its text is near illegible. However, the text, circular form of the shaft, and large stone base are a striking and distinctive survival of a monument type better known from among the Mercian rivals of the kings of Powys who erected this monument. Likewise, the cross-shaft, with its swags, has ninth-century paralles from Cumbria and is a distinctive early medieval form.

What is particularly lacking is any evidence from the excavations of ninth-century activity. While post-excavation work might reveal further traces, our dig didn’t reveal conclusive evidence of the site’s use as a settlement, burial ground or anything else for that matter. This isn’t surprising, since identifying any of these activities from archaeological evidence from Western Britain in this period is a huge challenge.

Prehistoric Origins

Finally, at the top of the genealogy is the prehistoric evidence: we have conclusively and convincingly shown that the mound beneath the Pillar was a multi-phased Bronze Age kerbed cairn with at least three secondary cists. Only one of the cits we dug was found to be undisturbed. In this one, the cremated remains of multiple individuals – adult and children – and artefacts (a bone pin and flint scraper) were found. This form of mortuary practice is well attested from North Wales, but this conclusively demonstrates a prehistoric data for the monumental sequence.

Conclusions

Post-excavation work on Project Eliseg is ongoing. Still, this brief sketch of some aspects of the monument’s biography reveal the changing fortunes and perceptions of the mound and Pillar and the practices that enwrap it.

A further point to be made about the cross – from its ninth-centur origins to the present – is a multmedia monument. Text, form and materiality, as well as its location on an ancient mound in a prominent valley terrace location, worked together to construct a monument claiming descent from ancient warleaders and saints. These could collectively and individually legitimate successive elite identities and authorities.

The irony is that the specific commemorative aspirations of this monument by those that commissioned it was unsuccessful. Concenn’s dynasty and kingdom did not survive the Viking Age. And yet this ‘failure’ opened it up to other perceptions and uses down the centuries, securing its persistence as a landmark in the Vale.