Grace Horsley Darling by Thomas Musgrave Joy. Reproduced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Darling

Grace Horsley Darling (1815-42) is one of the Victorian era’s premier heroines and her story is well told by the website dedicated to her memory. Grace was born in a cottage next to St Aidan’s Church, Bamburgh, Northumberland.

She grew up a lighthouse keeper’s daughter upon Brownsman Island, one of the Farne Islands. Adept at sea and familiar with seabirds and island life, she then moved aged 10 into the newly built Longstone Lighthouse in 1825.

On 7th September 1838, she observed the wreck and survivors of the Forfarshire and subsequently rowed with her father in a storm to their rescue. Grace was a young woman who lived a relatively isolated life who through her heroism became a worldwide early Victorian celebrity.

The Victorian obsession with this female celebrity (including fascination from clergy as well as laypeople) was replete with Christian spiritual allusions connecting her residence and acts and the deeds and habitations of the early saints Aidan and Cutbhert who inhabited the Farne Islands. Grace also embodied the adventurous romance of the sublime isolation and dangers of this maritime environment.

Yet the affinity for Grace manifest itself in the deeply, material and corporeal one desire to possess her body. People wrote fan mail to Grace, wished to kiss the paper and post it back, send locks of her hair, asking her to appear at public events as a ‘token’ and almost as an living saintly icon. People travelled to see her and there was a desire to have her act of bravery depicted by artists. Also, portraits of this lady were taken and widely distributed. Grace embodied the virtues of English Christian virginal womanhood. Whether it was the pressure of her fame alone, Grace died only four years later, aged only 26, on 20th October 1842. Perhaps she was hounded to an early grave by her public exposure; near her end she was fearful of imagined eyes watching her. Still, she was ultimately diagnosed with tuberculosis and died from that condition.

![Grace Darling gravestone. After Wikimedia Commons. By Nicholas Jackson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://howardwilliamsblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/256px-grace_darling_gravestone.jpg)

Grace Darling gravestone. After Wikimedia Commons. By Nicholas Jackson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

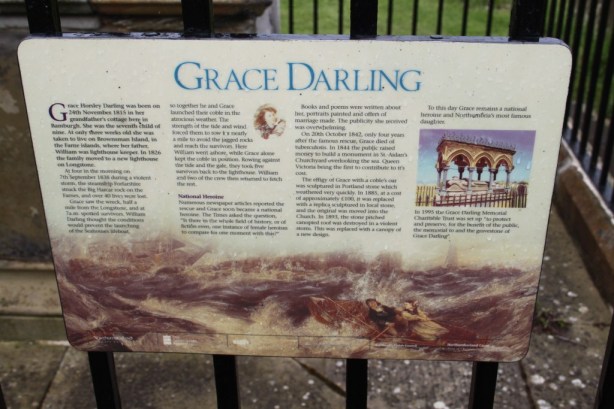

Yet soon after a more grand monument, a cenotaph, was constructed to her memory in the churchyard of St Aidan’s Church. Upon an elaborate canopied tomb-chest was a full-length effigy of Grace in simple gown with a coble’s oar lain on her right shoulder. As such Grace was afforded an aristocratic neo-Gothic memorial of comparable scale to those of aristocrats and bishops within contemporary cathedrals.

Yet her memorialisation has an interesting biography. For the Portland stone rapidly weathered in the open-air with views over the North Sea and it was brought inside St Aidan’s church and situated in the north aisle of the nave in the 1880s. A modern sign adjacent to it implores the visitor to pray for the souls of sailors and seafarers alike. Adjacent to this memorial is a small floor plaque marking the burial spot in 1903 of her relative and namesake Grace Horsley Kidd (born Darling).

![By Nicholas Jackson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://howardwilliamsblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/256px-grace_darling_memorial-1.jpg)

St Cutbhert’s chapel memorial. By Nicholas Jackson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The detail of the memorial is interesting. In addition to the presence of her oar over her right shoulder, she sleeps on a mattress that itself is upon kelp.

So Grace’s memorialisation was distributed between three loci: her grave, her extramural cenotaph and her intramural cenotoph. Both cenotaphs contain effigies of her with oars.

Further memorials proliferated. A stained glass window in the church beatifies her once again, and again she is depicted with a single oar. A memorial was established for her at St Cuthbert’s Chapel with a poem honouring her valiant deeds in the face of the stormy seas.

Grace has been memorialised in song, in art and also in the landscape of Northumberland sea rescue. The Seahouses lifeboat is called ‘Grace Darling’ and the RNLI Grace Darling museum is opposite St Aidan’s church, adjacent to the cottage in which she was born.

Yet despite this proliferation of memorial media, it is clearly her female body, through representation, that is the focus of popular desire and binds together disparate memorial projects.

My archaeodeath perspective sees this as:

(a) a classic example of how the dead don’t bury (or memorialise) themselves, and this particular young lady’s memory and reputation was utterly public and completely controlled and suppressed by the cultural ideal into which she was embedded. Both as a celebrity in life, and subsequently after death was a process of ‘dying into’ a form of secular sainthood as Christian heroine.

(b) a fascinating case of the distribution of social memory through a nexus of materials, spaces and places, in which multiple memorials within and without the church form a focus. Here, tombs operate because of their connections, planned or accrued, rather than their singular statements and subjects.

(c) this is an intriguing instance where, to honour a working-class heroic woman, early Victorian commemoration goes way back to medieval sainthood and depicts her with a token of her identity as rescuer and seafarer: the oar. Here, the oar is not literally the object of her martyrdom, but it is a symbol, a visual grave-good, of her singularly saintly and heroic identity in facing the raging storm to save the lives of those in distress. Below are images of the intramural and extramural monuments honouring the life of Grace Horsley Darling.

I have a life long interest in the RNLI and living in Exeter came across a memorial to Grace Darling at St. Thomas parish church in Exeter sadly in need or restoration.