Re-posted from Archaeodeath

This is my fourth and final comment about a short visit to Lindisfarne. The principal reason for my visit was to view the early medieval stone sculpture in the visitor centre and priory. Strip away the archaeological excavations elsewhere on Holy Island, strip away the historical record, the vast majority of the material evidence that this had been an important monastic foundation of the seventh to ninth centuries AD comes from the collection of Anglo-Saxon sculpted stones discovered in and around the priory. It is a fabulous and varied collection as one might expect. I have already mentioned the Petting Stone. In the priory itself is a cross-base with serpentine crosses on its front.

The rest of the sculpture on display is in the English Heritage visitor centre attached to the priory. I have already discussed the stone depicting warriors upon it, a possible gravestone with apocalyptic scenes.

The exhibition does a good job of communicating the potential wide range of functions that these fragments of stones might have once possessed, displaying the fragments themselves in categories like: ‘focal point of worship inside’, ‘marking a well’, ‘market cross’, ‘boundary stone’, ‘grave cover’ and so on. There is suitable text and (in most cases) adequate lighting although it is disappointing that the stones have to be bound around with metal wire to hold them in place.

Unfortunately, many of the stones are ornamented on two, three or more faces, and so many stones cannot be fully viewed. A few are placed in centrally placed display cases, or else mirrors are utilised to help the visitor appreciate the front and back of some stones. Yet for others it is evident that a choice has been made regarding which side to show and which not to show.

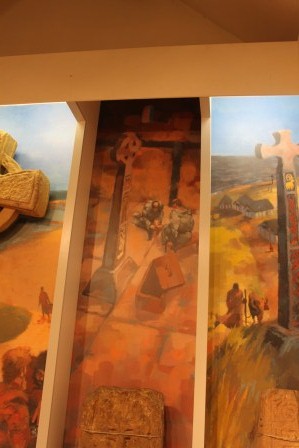

Art

The artwork helps the visitor a great deal to place these crosses into a context of human society and landscape context, even if much of this is informed speculation.

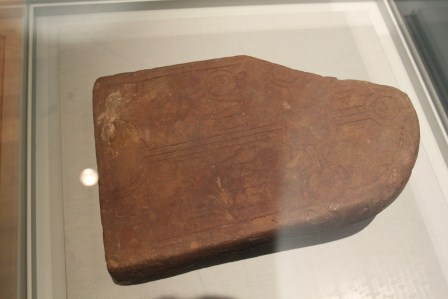

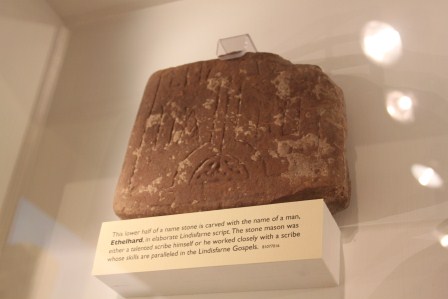

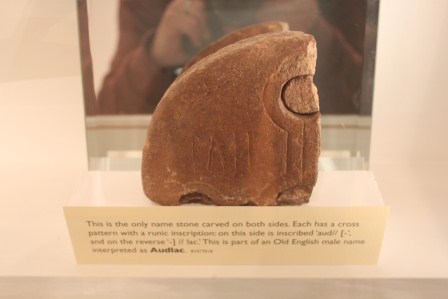

Name Stones

The collection of name stones are far smaller but far more impressive. Similar stones are known from other Northumbrian monasteries. Their scale fascinated me, for while some might plausibly be gravestones, some are so small I simply cannot envisage their function in this regard. There is a view of the name stones as apocalyptic grave-goods buried with the dead, and I think this interpretation makes far more sense of their scale and detail.

Here we find another strategy for display is a display case with two replicas of the Osgyth and Beannah stones, painted in striking colours informed by X-ray fluorescence of the stones: a white base was covered with red, green and black. For me, this was particularly informative, since it made me wonder how much these stones would resemble caskets and book-covers.

I hope these photographs and brief text encourage you to visit Lindisfarne and enjoy the exhibition and priory yourself.