Re-posted from Archaeodeath

As a place of worship and pilgrimage, with St Mary’s church and churchyard right next to the priory ruins, and given the long-standing associated with the absent saintly dead in the form of Aidan and Cuthbert, it is hardly surprising that death and memory are interwoven with the site of Lindisfarne Priory’s ruins. I have mused over the landscape and seascape context and the heritage interpretation of the famous Viking raid, but what of death and commemoration in the English Heritage site of Lindisfarne Priory and its environs? Even a brief consideration of this topic reveals the complexity of what is memorialised and what is not; where memorialisation has historically been allowed, and where it is not.

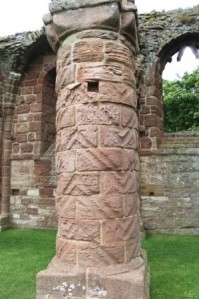

The ruins are a marvel in themselves, already one of my favourite sets of Romanesque and Gothic monastic ruins before I even got there. I loved the patina of the windblown sandstone and the fabulous columns of the nave, so reminiscent of Durham Cathedral. Here are some standard photos for your viewing pleasure.

For our purposes, what is striking is that, while the ruinous state has blurred the distinction between inside and outside, English Heritage has preserved the sense of sacred purity: the ruins are clear of all memorials.

I should add that there is the base of an Anglo-Saxon cross within the ruins, just as there is a collection of Anglo-Saxon stone sculpture in the visitor centre, some of which had an overt commemorative function. In this regard, the ruins and visitor centre combine to commemorate the lives of former inhabitants, named and unnamed. But this is a specific focus for the commemoration of saints and the more recent dead. The absence of a location and form to Cutbhert’s empty tomb is palpable, but there was art to fill the void in the form of a rather trangendered scuplture that might (or might not) represent St Cuthbert… (anyone who knows do get in touch and let me know!). So the ruins operate as a form of ‘sacred void’ where commemoration is eschewed. Thus, I was neither surprised or disappointed that there wasn’t a ‘St Cutbhert was buried here’ sign, in stark contrast to Glastonbury Abbey’s one for the grave of King Arthur…

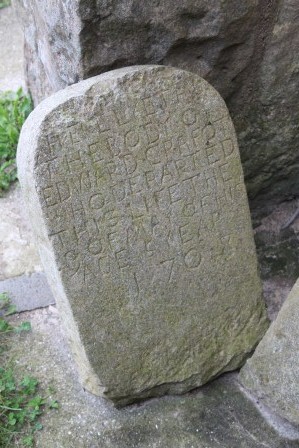

Of course the surroundings of the priory are the historic churchyard of St Mary’s. Positioned near the church are some fabulous 17th-century gravestones. Their ‘display’ in a prominent location beside the church is a typical strategy for dealing with such ancient and displaced memorials.

Meanwhile, the churchyard contains some eclectic memorials of 18th and 19th century date as well as more recent ones. I am not sure when burial rites ended in this churchyard and I didn’t stay long enough to find out where the modern cemetery is located (views please!).

Meanwhile, the churchyard contains some eclectic memorials of 18th and 19th century date as well as more recent ones. I am not sure when burial rites ended in this churchyard and I didn’t stay long enough to find out where the modern cemetery is located (views please!). Others seem to honour the churchyard boundary in a distinctive way, perhaps because of the specific interplay here between the presence of St Cutbhert’s Isle just over the wall. Thus St Cutbhert’s Isle is invisible to anyone in the churchyard, unlike Lindisfarne Castle and the priory ruins that frame the eastern view. However, anyone going right up to the churchyard boundary where these monuments are located will be rewarded with a view over this holy place. As such this is an interesting and specific example of the attention afforded to a particular boundary for the visual visibility/invisibility dynamics they create with the maritime surroundings and their holy history.

Others seem to honour the churchyard boundary in a distinctive way, perhaps because of the specific interplay here between the presence of St Cutbhert’s Isle just over the wall. Thus St Cutbhert’s Isle is invisible to anyone in the churchyard, unlike Lindisfarne Castle and the priory ruins that frame the eastern view. However, anyone going right up to the churchyard boundary where these monuments are located will be rewarded with a view over this holy place. As such this is an interesting and specific example of the attention afforded to a particular boundary for the visual visibility/invisibility dynamics they create with the maritime surroundings and their holy history.

I also observed some rather overt and pretentious attempts to invoke the Anglo-Saxon origins of the monastery through grostesque Victorian/Edwardian high-crosses. You cannot tell me that people didn’t look at this and resent the imposition of this monument, especially because of its location right outside the west door of the priory. Indeed, I wonder if this juxtaposition inspired the similar location for the Boer War memorial outside Durham cathedral…

A further dimension to the churchyard is the base of an genuine Anglo-Saxon cross – the Petting Stone – that has an interesting ‘afterlife’, unless the rest of the stones that have been relocated for display as archaeological remains. This particular monument has been a long-standing focus of a fertility ritual in which each new bride is lifted over it following their marriage in the church. Cross-bases bring fertility!

A further memorial dimension is a statue: framing the approach to the priory ruins and St Mary’s church, of either St Cutbhert or St Aidan (I couldn’t see an inscription telling me which). Did I miss it or is it overtly ambiguous?

Immediately adjacent to, and overlooking the priory, the Heugh is another focus of recent commemoration, with memorial benches and Lindisfarne’s war memorial: commemorating the island’s dead of both world wars and positioned to view both inland and out to sea.

Therefore, linking together many of these memorials is a tension between location and dislocation, between place and the landscape in which that place is situated upon an island, between voids and presences. It seems that there is a fascinating study to be done here of holy sites that are also visitor attractions and heritage sites, and how different forms of commemorative practice interleave with each other at these locales.