Reposted from Prof. Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog, this post explores the Vale of Llangollen in the Early Middle Ages.

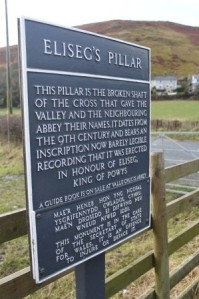

- The Pillar of Eliseg

I here summarise the paper I presented at this year’s EMWARG conference. I focus on the landscape context of the Pillar of Eliseg, a subject of numerous previous talks and blog entries on the Archaeodeath site.

Introduction

Stone monuments of the Early Middle Ages are profitably considered as an important commemorative medium. They were more than stores of social and religious memories for early medieval individuals and communities through their carving and placement. They also constituted memories through the stone’s provenance, translation, installation and subsequent ongoing and shifting contexts of use and reuse. In these intertwined fashions, stone monuments were key components of early medieval memory work. We might regard them less as repositories of memories, but as technologies of remembrance that enchained people through practices to particular visions of past, present and future. This approach foregrounds early medieval stone monuments as components in what Paul Connerton helpfully refers to as inscribing practices – acts of inscription and collective ritual – and incorporating practices – including embodied and habitual actions of engagement.

Integral to this approach to early medieval stone monuments are three themes: materiality, biography and landscape.

- Materiality: Recent work has revised and overhauled our perspectives on the commemorative materialities of stone monuments. Readings of the form, imagery, ornament and text inscribed on stone have increasingly been situated in relation to interpretations of other material dimensions including stone provenance, mass, texture, colour and patina. The deliberate allusions and interplay between commemorative media – skeuomorphism – is also a key focus of enquiry.

- Biographies: Over the last two decades in particular, work has increasingly engaged with the biographies of monuments. This work regards stone monuments less as commemorative ‘moments’, but as unfolding projects looking back to their sites of extraction and production and forward to their use, reuse and relocation).

- Landscape: The third element is the principal focus of this paper. Over the last decade in particular, there has been a more careful consideration of the spatial settings and relationships between stones within sites and locales, and their wider landscape situation. Hampered by difficulties of locating contexts for many stones, for those in situ or with possible and probably contexts, attention has been drawn to the reuse of prehistoric and Roman stones and the reuse of prehistoric and Roman sites as settings for monuments. Furthermore, relationships with routes, boundaries, settlements, religious sites (chapels, shrines, holy wells) and burial sites as well as the relationship with topography, vegetation and view-sheds have received increasing consideration.

These themes are the focus of a forthcoming book project that I am co-editing.

The Pillar of Eliseg

As a case study in approaching early medieval sculpture as memory work in which each of these three themes are pertinent, I wish to explore recent work on the Pillar of Eliseg near Valle Crucis Abbey, Llangollen, Denbighshire, also known as Llandysilio Yn Iâl 1 (SJ 2027 4452) (Edwards 2013: 322-336). Situated to the western side of the Nant Eglwyseg, this striking and unique-for-Wales monument is dated through the text upon it, to between AD 808 and around 854/55. Raised by the ruler of Powys, Cyngen ap Cadell, its lengthy Latin inscription honours his great-grandfather Elise ap Gwylog and his military victories against the English (presumably the Mercians during the last years of the reign of King Aethelbald and the early years of the reign of King Offa) and the subsequent recovery of Powys, possibly around AD 757 (Charles-Edwards 2013: 417). It might be the case, but not proven because of the partial survival of the text when transcribed in the 17th century by Edward Lhuwyd, that Cyngen ap Cadell himself made a similar, parallel recovery at the beginning of his kingship following subsequent Mercian incursions early in his reign by Cenwulf (Charles-Edwards 2013: 418-19). If so, the Pillar might be regarded a victory monument that juxtaposes, compares and celebrates together the restorative military endeavours of multiple generations of the rulers of Powys.

The Pillar’s text, form and materiality worked together. In her 2009 Antiquaries Journal article, and subsequently in her 2013 Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales, Professor Nancy Edwards presents a reinterpretation of the text as political propaganda. She also considers how the material form of the script – Latin half-uncial – makes sense in the context of a land charter. Its performative nature is explicit in the text: it was to be read out loud. Furthermore, the cylindrical form of the shaft may have evoked Roman triumphal columns and its location on a far-older mound were key to the text’s commemorative message linking imagined pasts to the present, honouring the legendary forebears, immediate ancestry and current household of the rulers of Powys. Presenting a contrasting history of the origins of Powys to the Historia Brittonum descending from a positively viewed Vortigern, married to the daughter of Maximus, the cross reveals the competitive, conflicting and temporal manipulations possible in ninth-century genealogies and origin myths (Charles-Edwards 2013: 449-50).

Together, these disparate multi-media commemorative monument projected Cyngen and Confarch’s aspirations to lordship and military might forward into the future together with their hopes of eternal salvation. Edwards suggests that the monument may have served as an assembly place and possibly served, or was intended to serve, as a site of royal inauguration. Furthermore, through her detailed attention to the monument’s life-history, Edwards not only reveals the origins of the cross, but also shows its persistent presence in the landscape over eleven hundred years. I have previously regarded this as the creation of a cyclical transtemporality through text and context, concerned as much with projecting an aspired future as recollecting a distant past (Williams 2011).

Project Eliseg

The materiality and biography of the Pillar of Eliseg have been revealed further still through the ongoing research of Project Eliseg (Edwards et al. 2010; Edwards et al. 2012). This collaborative fieldwork project between the universities of Bangor and Chester and supported by Llangollen Museum and Cadw has received generous support from a number of funding sources, including the Society of Antiquaries of London, the Prehistoric Society, the Cambrian Archaeological Association, the Aberystwyth and Bangor Universities’ Institute of Medieval and Early Modern Studies University of Wales, Bangor University, University of Chester and Cadw. Co-directed by Dai Morgan Evans, Gary Robinson, Nancy Edwards and myself, we have attempted to enhance and extend our understanding of the commemorative programme of the Pillar of Eliseg. Three seasons of work on and around the mound took place in the summers of 2010, 2011 and 2012 (http://projecteliseg.org/).

I have discussed the project in many previous blogs such as here. Our fieldwork was restricted by working on a scheduled site, excavating only a small sample in the area deemed most disturbed. It is evident that the monument as a whole has been heavily disturbed through barrow-digging, vegetation, animals and human visitors, and retains the important restriction of having on top of it a very heavy re-arrangement of fragments of a ninth-century cross. Still, our project has seen moderate successes, although post-excavation work is ongoing and results and interpretations presented below remain interim.

Following on from a geophysical survey conducted by Alex Turner and Sarah Semple, the 2010 season examined without result a concentration of geophysical anomalies in the field to the north of the mound. We also stripped areas of the mound to reveal its surface appearance beneath the turf. In 2011, we began excavating into the mound on its western side, revealing multiple stages to its construction and revealing burial cists. In 2012, we returned to complete our work, excavating three burial cists – one proving to be undisturbed and packed with cremated human remains of at least 8 individuals. We also completed our field recording, as well as conducting a detailed topographical survey of the mound and its environs.

Materiality and Biography

In terms of biography and materiality, we await final confirmation from radiocarbon dating, we have found conclusive artefactual, monumental and stratigraphic evidence that suggests that the mound was originally a kerbed cairn of Early Bronze Age date. It was subject to a sequence of secondary burials and structural augmentation over an as-yet unspecified duration. Unfortunately, we found no conclusive evidence of early medieval reuse of the mound, although the largest cist, empty when excavated, could have originally contained a burial of any date from the Bronze Age to the Early Middle Ages.

Still, the composition and character of the mound helps us understand how the mound was perceived in the Early Middle Ages and selected as a site for raising a striking royal stone cross upon it. What became clear during excavation was that the superficial location of the secondary cists we discovered. We know that, by the ninth century, there was a long tradition of burial associated with ancient monuments in the Welsh landscape. Moreover, monuments were becoming mythologised, evidenced by broadly contemporary sources such as the Stanzas of the Graves (Petts 2007; Edwards 2009). Yet the superficial position of the cists prompts to imagine it was extremely likely that anyone encountering and superficially digging into the mound in the Early Middle Ages would have uncovered comparable secondary cists, if not these very ones (given that two out of three were disturbed). Indeed, digging need not have been necessary: cists may have eroded out and been exposed upon surface inspection, then as now, especially on the steep southern side. Therefore, while there are no surviving folkore and legends associated with the mound, this evidence hints that the mound would have been understood to be a funerary monument: in ‘theory speak’, the Bronze Age cists had an agency, encouraging the mound’s reuse in future generations, if not the specific character of its reuse.

The balance of evidence suggests that this was a long-abandoned prehistoric monument reactivated through use as a cross, but by individuals conscious that the mound was an ancient burial monument. Still, there is an account of excavations in the 1780s, prior to the re-erection of the Pillar, describing the discovery in the centre of the mound of a stone box containing a skeleton box with a silver disc. Edwards (2009; 2013) makes clear her view that a Bronze Age burial mound is an unlikely context for an eighth-century high-status burial. Certainly our excavations did not, and could not, secure a view on this matter either way: we had no permission to remove the heavy stone sculpture to investigate what lay beneath the centre of the mound. Still, given:

- the possibility that mounds continued to attract burials away from church settings across early medieval Britain long after Christian conversion (bearing in mind how difficult it is to date the end-date of many early Christian cemeteries excavated in North Wales: see Longley 2009).

- that we cannot be sure that the mound was not part of a Christian church focusing on the site that was to later attract a Cistercian foundation (bearing in mind that early Christian church sites might have multiple burial foci, some focusing on anceitn mounds, as at Repton, North Yorkshire, Hall and Whyman 1996).

- given that while most early medieval burials in Wales are findless, if accurately reported, a ‘silver disc’ could refer to all manner of artefacts – coins, disc brooches – that can occasionally, if rarely, be found in early medieval graves of the later seventh and early eighth centuries.

In the light of these points, we still shouldn’t rule out the possibility that the cross was part of a longer series of early medieval activities on the site, including its eighth-century reuse as a burial monument to honour Elise or other members of the ruling dynasty of Powys. Either way, we have demonstrated that the choice of site mobilised links to the ancient past, a mythologizing of place that mirrors the text and form of the monument (Petts 2007, 166; Edwards 2009, 149-51; 2013).

Our excavations also revealed traces of post-medieval activity on the mound, antiquarian disturbance and further indications regarding how the fragments were re-erected over the mound in the late eighteenth century, so the longer biography of the monument has been informed by our fieldwork.

The Topography of Memory

Nancy Edwards has explored varied dimensions to the landscape contexts of early medieval stone sculpture (Edwards 2001a and b; 2007). Yet both Edwards’ research and the fieldwork by Project Eliseg have been both focused upon the mound rather than the wider landscape (Edwards 2009; 2013). Hence, much remains to be explored regarding the wider early medieval landscape in which this striking commemorative cross was situated. How was the location integral to the commemorative project of the monument in the ninth century? Here, I would advocate that we need to think about the location from a multi-scalar perspective, thinking first about the immediate environs, then the wider Vale of Llangollen.

My working hypothesis is that, as I have argued previously, crosses like this need to be regarded as pivots within early medieval topographies of remembrance, located spatially and conceptually at the intersection between secular elites and sacred commemorative traditions focusing on churches (Williams 2006, 192). I have outlined some tentative suggestions regarding how the monument may have operated as a commemorative landmark informed by previous research and a sense of the topography surrounding the site today (Williams 2011). This year brings the opportunity to test these ideas further, as part of the interdisciplinary Past in its Place project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and the European Research Council, I am working with Drs Patricia Murrieta-Flores (University of Chester) together with other project researchers to explore further the topographies of memory revealed in archaeological, historical and literary sources from the eastern part of the Vale of Llangollen. In the context of this ongoing research, I want to outline some tentative observations regarding the landscape context of the Pillar of Eliseg.

Place and Performance

Topography, metal-detector finds and aerial photographs combine to support and extend Edwards’ 2009 suggestion that the Pillar of Eliseg was one node in a assembly or central place. The site may have operated as a theatre for large gatherings and there are hints that high-status settlement and/or other ceremonial spaces were located in its proximity

Movement and Memory

I presented a series of strands of evidence to suggest the key relationship between movement through the landscape and the location of the Pillar as a mnemonic landmark. I argued that the Pillar was located in a topographical bottle-neck and a zone of movement in and out of the Vale. I also put forward the suggestion that the movement of the stone to the site was also a ‘translation’ that was memorable. Together, movement and memory were intertwined in making the monument’s text, form and materiality effective as a commemorative medium.

Sacred and Military Landscapes

I reviewed the latest evidence regarding what we know about the sacred and political geography of the Vale of Llangollen, a subject for which far more work is required. I suggested that the Pillar was located at a defensible location as well as an accessible one and related to both secular and religious networks of places and routes. The cult site of St Collen (Silvester and Evans 2009), the well of St Collen and a possible church site beneath the later abbey were discussed. Whilst hillforts are dated in the region to the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (e.g. Grant 2010), I explored the possibility that many were reused in the Early Middle Ages for a range of functions, providing a further settlement context for the Pillar. I also argued that the relationship with the near-contemporary early ninth-century Wat’s Dyke needs further attention and interpretation (Malim and Hayes 2008), and possibly also to short-dykes of unknown date (Silvester and Hankinson 2002), alongside established discussions of the Pillar in relation to Offa’s Dyke (Hill 2000).

Conclusion

Project Eliseg has been very much about breaking into the monument – using archaeology to investigate the mound’s biography and materiality. I have previously referred to this as the Pillar of Eliseg’s prison break. In this paper, I presented the flip-side, because the archaeological work as part of the Past in its Place project is very much about breaking out, resituating the Pillar within a series of landscapes. This is a multi-scalar approach to understanding how the monument may have operated and functioned in the early medieval landscape and subsequently through the Middle Ages to the present day with regards to topographies of memory.

References

Charles-Edwards, T. 2013. Wales and the Britons 300-1064, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Edwards, N. 2001a. Monuments in a landscape: The early medieval sculpture of St David’s, in H. Hamerow & A. MacGregor (eds) Image and Power in the Archaeology of Early Medieval Britain, Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 53-77.

Edwards, N. 2001b. Early medieval inscribed stones and stone sculpture in Wales: context and function, Medieval Archaeology 45: 15-39.

Edwards, N. 2007. A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales. Volume II, South-West Wales, Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Edwards, N. 2009. Rethinking the Pillar of Eliseg, The Antiquaries Journal 89: 143-77.

Edwards, N. 2013. A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales. Volume III, North Wales, Cardiff: University of Wales Press

Edwards, N., Robinson, G., Williams, H. and Evans, D.M. 2010. The Pillar of Eliseg, Llantysilio, incomplete inscribed cross and cairn, SJ 2027 4452. NPRN 101160; 101161, Archaeology in Wales 50: 57-59.

Edwards, N., Robinson, G. and Williams, H. 2012. Project Eliseg: Preliminary Report Prepared for Cadw, December 2012. Unpublished Report.

Grant, I. 2010. Moel y Gaer hillfort, Llantysilio, Denbighshire, Archaeological Excavation. CPAT Report No. 1059.

Griffiths, D. 2006. Maen Achwyfan and the context of Viking settlement in north-east Wales, Archaeologia Cambrensis 155: 143-62.

Hill, D. 2000. Offa’s Dyke: pattern and purpose, Antiquaries Journal 80, 195-206.

Longley, D. 2009. Early medieval burial in Wales, in . Identifying the mother churches of North-East Wales, in N. Edwards (ed.) The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches, Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 29. Leeds: Maney, pp. 21-40.

Malim, T. and Hayes, L. 2008. The date and nature of Wat’s Dyke: a reassessment in the light of recent investigations at Gobowen, Shropshire, in S. Crawford and H. Hamerow (eds) Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 15, Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology, pp. 147-79.

Petts, D. 2007. De Situ Brecheniauc and Englunion y Beddau: Writing about burial in early medieval Wales, in S. Semple & H. Williams (eds) Early Medieval Mortuary Practices, Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 14, Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology, pp. 163-172.

Silvester, R. J. and Hankinson, R. 2002. The Short Dykes of Mid and North-East Wales. March 2002. Welshpool: Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust.

Silvester, R. & Evans, J.W. 2009. Identifying the mother churches of North-East Wales, in N. Edwards (ed.) The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches, Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 29. Leeds: Maney, pp. 21-40.

Williams, H. 2006. Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.