From Howard’s Archaeodeath blog. The churchyard of St Philip’s, Birmingham Cathedral, might be regarded as a useful place to ruminate on the futility of remembrance. Over 60,000 bodies are thought to have been interred here between the church’s opening in the early 18th century until its closure for burial in 1859. So few of these received a memorial and only a tiny fraction of these have survived to be viewed today. Commemorate as we might (as Bill and Ted once said, citing the epic masterpiece by Kansas) all we are is dust in the wind... dude.

Death and Memory Inside Birmingham Cathedral

From Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog.

From Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog.

Recently I had the opportunity, as part of the Past in its Place project, to visit Birmingham Cathedral and explore its memorials together with my doctoral student Ruth Nugent. We met their new and superbly helpful Heritage Manager, Jane McArdle, and explored the churchyard and inside the cathedral church itself.

In previous blogs, I have outlined some of the interests we have in cathedral commemoration over the long term here and here and here and here and also… here.

Tangible and Intangible Pasts

From Howard’s Archaeodeath blog.

I want to discuss the tension between tangible and intangible heritage in specific relation to social memory in British landscapes with complex multi-period collections of monuments. My example is White Horse Hill.

This might be old news to many of those working in the profession and academia, but it is something that I have only begun to think about regarding mortuary archaeology and the spaces I am investigating as part of the Past in its Place project; cathedrals, ancient habitations and topographies of memory involving monumental and literary traces.

The textual and material traces of all our sites and landscapes of investigation have dimensions that are still today tangible: including monuments, buildings, memorials. Others are no longer visible but might be apprehended in books. Texts on things, things on text, as well as many, many text-less things and material traces. Yet these dimensions persist and interleave with many traces that are now hidden, stories that are only known indirectly, many intangible dimensions and facets.

Therefore, situated between the tangible and the intangible are traces that are seemingly imperceptible to the casual visitor because of their scale; their grand dimensions or their sleight proportions, as to render them poorly defined as either a fully ‘material trace’ or as an intangible presence. For example, is a management scheme for maintaining grassland through sheep grazing a ‘thing’ that is fully perceptible? Are hut circles, denuded round barrows, field systems only visible from the air perceptible or imperceptible? A bit of both, but in very different ways, is surely part of the answer. For example, a hillfort is both perceptible and imperceptible: some elements are monumental, others only known from archaeological excavation and survey. Other bits have long gone. What is ‘man-made’ and what is ‘natural’ in such a landscape?

Speaking with Effigy Tombs

Medieval Lordly Tomb, Worcester Cathedral

From Howard’s Archaeodeath blog.

Here are some very basic musings about tombs in cathedrals prepared for the Speaking with the Dead exhibition at Exeter Cathedral. Church monument experts: expect to find errors and happy to be corrected and additional examples pointed out.

Introduction

Effigy tombs are complex, varied, striking and prominent monuments to the elite dead which can dominate even the largest of cathedral churches. These space-gobbling monuments can be placed in wall-niches or free-standing within cathedral aisles, chapels or transepts. They are among the most interesting to visitors and most commented upon monuments for any cathedral.

These are body-centred monuments. Effigy tombs (and effigy slabs) depicted the dead in prayer or holding artefacts that denote their office and identity. The sculpted bodies wore costumes befitting the deceased’s status or rank held in life and that aspired for recognition in Heaven.

Recipients of effigy tombs included archbishops, bishops, abbots, deacons and priests. For the secular elite: royalty, nobility, gentlefolk were sometimes joined by lower social classes. Continue reading

Cremation and the Cathedral

From Howard’s Archaeodeath blog.

As part of Strand 1 of the Past in its Place project – Speaking with the Dead – I am writing (with my PhD student Ruth Nugent about cremation and cathedrals) in England and Wales.

In considering cathedrals as environments for ongoing literary and material engagements between the living and the dead, it would be easy to dismiss the last 150 years as a time of commemorative decline. Scholarship on monuments and memorials bears out this impression. After all, the vast majority of scholarly research on cathedral memorials has focused on medieval shrines and effigies, early modern mural monuments, and sometimes the grandiose edifices of Victorian clergy.

Our research suggests the contrary. By looking at a sample of English and Welsh cathedrals to reveal wider trends and practices in cathedral commemoration, the Speaking with the Dead project has identified that cathedrals have sustained and adapted themselves as nodes in a complex topography for remembering the dead. While burial in cathedrals has all but ceased in the late 19th century, cenotaphs to bodies interred elsewhere, and memorials to the cremated dead, persist as key dimensions of how cathedrals operate as places of memory. Furthermore, the ashes of the cremated dead have, during the 20th century, increasingly reached into cathedral commemorative environments long denied to unburned cadavers following Victorian legislation against intramural and inner-city burial.

While lengthy, eloquent epitaphs are all but absent, this memorial tradition remains textual, in an abrupt, formulaic and thus powerful and conservative fashion. Furthermore, these memorials gain their significance both individually and collectively, through their integration into the pre-existing fabric of medieval buildings and their surroundings. Memorials to the cremated dead also gain significance through their close association and reuse of far older aisles, chapels, monuments and memorials: often place side-by-side with the tombs of medieval bishops and Jacobean aristocrats.

How are the cremated dead memorialised through materials, texts and spaces in and around the modern cathedral?

- Churches and cathedrals have a long tradition of cenotaphic memorialisation since the Middle Ages, with memorials situated on/in walls, windows, floors and fittings (such as pews and lecterns) displaced from the bodies subject to commemoration. In many ways, memorials to the cremated dead are incorporated into this long tradition of memorialisation without the body that persists to the present day

- Long before cremation came back into fashion, cremation was implied in cathedral architecture from the late sixteenth century through to the nineteenth century. Mural monuments to aristocrats, and later regimental and war memorials, depict the hero’s tomb, flaming urns articulating the ascension of the soul to Heaven, lidded urns implying the idea of ashes therein, and torches used in antiquity to ignite funerary pyres.

- Since the late 19th century, memorials to burials in cathedrals become exceptional, yet memorials to bodies and ashes interred elsewhere persist. Many of the memorials in cathedrals allude indirectly to individuals who were cremated upon death. Only upon rare occasions is there an explicit reference to the memorialisation of ashes interred elsewhere.

- As cremation rose in popularity during the 20th century, interments of ashes for those closely connected to the cathedral were permitted beneath floor surfaces. In rare cases, this is made explicit in the text of the memorial, but far more often it is implied by the small size of the memorial and its location.

- During the twentieth centuries, burial grounds within cloister gardens either persisted, or were reused, to receive the interment and/or scattering of ashes. The walls and windows of cloisters continued to receive memorials to those whose ashes were scattered or interred therein, adapting a long existing cenotaphic memorial tradition.

- Both the long-defunct and still-operational burial grounds around cathedrals have been revitalised as spaces for ash dispersal, interment through burial plots and gardens of remembrance.

- Cathedrals are almost always situated in close proximity to one or more suburban cemeteries and crematoria built during the late 19th, early 20th or (most often) late 20th centuries. The funerals and memorial notable individuals and military groups have linked these spaces together.

In summary, despite the traditional ambivalence of many sections of Anglicanism to the rise of cremation, the disposal of the dead by fire has had a long-term impact, as idea and reality, on the commemoration of the cathedral dead since the early modern period and in particular during the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Mortuary Selfies: Photos from Among the Tombs

Reblogged from Howard’s Archaeodeath.

There is much outrage and indignation about the proliferation of ‘selfies’ extending into mortuary and dark touristic realms in the media of late. Boundaries of ‘taste’ have been infringed apparently. With this in mind, and nearing the completion of Strand 1 of the Past in its Place project, with a forthcoming exhibition about our work planned at Exeter Cathedral, it seems appropriate to post some photographs of the project team exploring the memorials and tombs of English and Welsh cathedrals.

As part of the project, we have been taking an exhaustive set of digital photographs of the memorials on windows, fittings, walls and floors in a series of English and Welsh cathedrals. This has presented all manner of methodological and practical challenges and I am not always pleased with the results. The advantages have been tremendous too, since we are focusing not only on the grandest monuments, but on the humble ledgers too. Hence, we are exploring the chronological and spatial variability of commemorative practices in and around cathedrals.

Incidentally and sometimes accidentally, Ruth and I have captured pictures of project members going about photographing and investigating memorials and tombs, talking with each other around memorials and tombs, and meeting librarians, archivists and archaeologists.

I didn’t go about this recording of other people in a systematic way, and likewise pics with me in are rare and accidental. In and around cathedrals where I was alone on my visit, there are few pics of myself. I wonder if these photographs will arouse anger and indignation. If not, this blog entry might simply be a bit self-indulgent. Still, they are not really ‘selfies’ in the usual sense, but in the collective project sense, they are photographs of ‘us’.

Be that as it may, like funeral selfies, it is not mere narcissism of myself and/or of the project. These photographs serve to document, to mark our presence in time and place, at different times of day, times of year, and in different English and Welsh places with long and complex ‘histories of memory’. We were there, we saw the tombs, we saw the memorials, we visited that place. As such, in a humble sense, they are a snapshot of the many thousands of pilgrims and visitors who, over the centuries, for different motives and different circumstances, have explored and inscribed, prayed and remembered, sung and sobbed among the tombs…. In many ways, this is exactly the kind of memory work our project is seeking to investigate.

Featured are Philip, Naomi, Paty, Ruth and various other scholars with whom with met at Norwich, Canterbury, St Albans and elsewhere.

Commemorating Cures

Although not about one of the sites that form a focus of the Past in its Place project, this recent blog entry explores the material practices taking place at sites of pilgrimmage, particulary from the 19th century. It is reblogged here from Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath site.

Recently I visited St Winifred’s Well, a tourist attraction and Christian cult focus at Holywell, Flintshire. For further details see their website here.

With twins in tow, I didn’t get a chance to walk around the museum, but I did get the opportunity to explore well chapel itself: the ‘Lourdes of Wales’. A focus of legend associated with the supposed 7th-century female saint. Wini lost her head to save her virginity from a rapist, and it miraculous was reattached. Headstrong Wini lived out her life a nun and her cult grew throughout the Middle Ages. The structure you can see is a phenomenal early 16th-century well-chapel with later additions during the 18th and 19th centuries.

As with all foci of veneration by pilgrims, there are various ephemeral material cultures that inhabit and augment this space, from candles to cards. There are also different forms of memorial.

Commemorating the Dead

The historic churchyard associated with and uphill from the chapel has now been cleared completely, but it is a strikingly steep space that reminded me of Coalbrookdale’s Quaker burial ground. Along its western edge there remain a collection of in situ and relocated memorials of 18th- and 19th-century date.

More recent memorials allowed in the chapel grounds take the form of our good old friend the memorial bench. These include a notable number to ladies named ‘Winifred’. Lining the route to, around and within, and from the well, these benches allow the dead to be remembered at, and presenced at, the holy well.

A further memorial or votive practice is placing potted plants and flowers around the statue of St Winifred in front of the well.

Commemorating Cures

The most prevalent historic form of memorial is the graffiti that adorns all surfaces, including notably the sites of the structure that face into the waters. The motives of inscribers are unclear: counter-souvenirs of the act of pilgrimage itself (i.e. marking the place been to rather than/or additional to bringing a memento back with the pilgrim), dedications of prayers to Saint Winifred for hoped-for cures, or commemorative statements celebrating cures received by pilgrims. There are forms of graffiti familiar from cathedrals where pilgrims have thronged around the crypts and shrines containing the remains of the saintly dead.

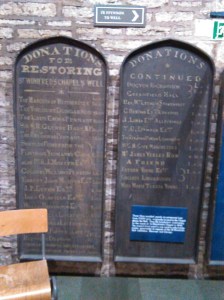

In the visitor exhibition there are wooden boards recording financial offerings to the chapel, as well as another form of discard; crutches left behind by cured pilgrims. Crutches were something I hadn’t encountered before as an assemblage of similar artefacts at a sacred site. They reminded me of the sinister display of artefacts in horrific piles at Auchwitz-Birkenau; the possessions – suitcases, shoes, cut hair etc – of those killed by the Nazi regime and serving as material testimony to this atrocity. Yet at St Winifred’s while the former owners are undoubtedly now dead, these artefacts commemorate cures and the lifting of suffering by saintly intercession.

Speaking with the Dead Exhibition at Exeter Cathedral

Events commemorating the start of World War I were everywhere today, but at Exeter Cathedral we were taking the longer view, with the launch of the “Speaking with the Dead” exhibition. Showcasing items from the Cathedral archives and collections alongside posters illustrating the research we have been pursuing over the last three years, the exhibition will occupy the north choir aisle for 10 days, before travelling on to St Albans (and perhaps beyond…). Philip Schwyzer and Naomi Howell gave a public lecture in the Cathedral’s Chapter House to mark the occasion. Those attending also had the opportunity to view the Cathedral’s unique and enigmatic funeral pall, stitched (it would seem) out of pre-Reformation vestments into an object of new and complex significance. (A comparable pall from the nearby church of St Mary Arches is on display in Exeter’s Royal Albert Memorial Museum.)

Although the unique wax votives associated with the tomb of Bishop Lacy are too fragile to be put on display, the exhibition features evocative replicas designed by Fiona Knott. Other highlights include the episcopal chalice of Bishop Bitton, found in his grave when it was opened in 1763; the Exeter Martyrology; the earliest manuscript monumentarium of the cathedral by J. Jones (1787); and condolence books inscribed by members of the public following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. The exhibition also features video and interactive displays, highlighting the innovative work of Patricia Murietta-Flores and Ruth Nugent in applying technologies such as Reflectance Transformation Imaging to the study of cathedral inscriptions and graffiti. Sarah Grainger, who designed the magnificent posters, was on hand to assist in arranging the displays.

Below, a selection of photos taken on the day.

Death-Defying Cistercians?

Re-posted from Howard’s Archaeodeath blog. In the Past in its Place project we are exploring how memories are located in cathedrals, ancient habitations and the wider landscape. Here, I muse over how the dispersal of tombs and memorials, and the heritage management of the ruins of Cistercian monasteries, is more than a casual ‘forgetting’ of the dead, but an overt dimension of heritage interpretation with its focusing on the religious and economic life of medieval monks that downplays the dynamic relationships between patrons and abbeys in which memory was key.

I recently visited Buildwas Abbey, Shropshire, a site managed by English Heritage and staffed that day by one of its most friendly of employees. Beside the River Severn, this is a perfect ruin of a 12th-century Cistercian house, suppressed in 1536 and adapted into a secular mansion.

It is truly a ‘perfect ruin’, together with woodland walks down to the river. It was a great stop-off en route back from Oxfordshire to North Wales. For me this was a real nostalgia visit, since I last went there as a kid myself. Here are some general pictures of this superb ruin with the neatly trimmed grass that typifies EH sites.

Cremation Switchback and the Churchyard

Pennant Melangell church

This is re-posted from Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog.

Recently I posted about a visit to Pennant Melangell and the shrine of St Melangell. Well, it must be said that this is a fascinating site for its church and internal memorials, but even more so for its churchyard.

Many urban,suburban and large rural churchyards (whether in use or abandoned) have very complex patterns of memorialisation with multiple foci to them. In such environments, the bodies of the dead compete with each other, jostling down the generations within the restrictions of limited space. From the 19th century in particular, some churchyards bear signs of a new trend of expansion rather than reuse.