Inaugurating a new tradition on the “Past in its Place” blog: Poem of the Week. Check back each week for a piece of immortal (or, sometimes, all too mortal) verse treating one of our Sites of Memory.

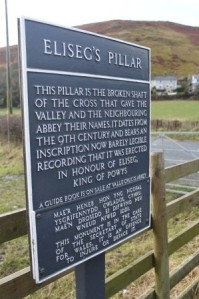

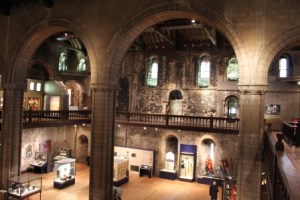

To begin with, here’s the Romantic poet Anna Seward’s “Llangollen Vale,” composed in 1795 following the Romantic poet’s visit to the celebrated Ladies of Plas Newydd, Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler. The Ladies and their “Fairy Palace” make their appearance a little more than midway through this 168-line poem, following a stirring if oddly inconclusive account of Glyndwr’s rebellion. The weepy, superstitious monks of Valle Crucis get a look-in toward the end. But, Seward wonders, did any young monastic lip ever wear “gay Eleanora’s smile”?

LLANGOLLEN VALE

Luxuriant Vale, thy country’s early boast,

What time great GLENDOUR gave thy scenes to Fame;

Taught the proud numbers of the English Host,

How vain their vaunted force, when Freedom’s flame

Fir’d him to brave the Myriads he abhorr’d,

Wing’d his unerring shaft, and edg’d his victor sword.

Here first those orbs unclosing drank the light,

Cambria’s bright stars, the meteors of her Foes;

What dread and dubious omens mark’d the night,

That lour’d ere yet his natal morn arose!

The Steeds paternal, on their cavern’d floor,

Foaming, and horror-struck, “fret fetlock-deep in gore.”

PLAGUE, in her livid hand, o’er all the Isle,

Shook her dark flag, impure with fetid stains;

While “DEATH, on his pale Horse,” with baleful smile,

Smote with its blasting hoof the frighted plains.

Soon thro’ the grass-grown streets, in silence led,

Slow moves the midnight Cart, heapt with the naked Dead.

Yet in the festal dawn of Richard’s reign,

Thy gallant GLENDOUR’S sunny prime arose;

Virtuous, tho’ gay, in that Circean fane,

Bright Science twin’d her circlet round his brows;

Nor cou’d the youthful, rash, luxurious King

Dissolve the Hero’s worth on his Icarian wing.

Sudden it drops on its meridian flight!—

Ah! hapless Richard! never didst thou aim

To crush primeval Britons with thy might,

And their brave Glendour’s tears embalm thy name.

Back from thy victor-Rival’s vaunting Throng,

Sorrowing, and stern, he sinks LLANGOLLEN’S shades among.

Soon, in imperious Henry’s dazzled eyes,

The guardian bounds of just Dominion melt;

His scarce-hop’d crown imperfect bliss supplies,

Till Cambria’s vassalage be deeply felt.

Now up her craggy steeps, in long array,

Swarm his exulting Bands, impatient for the fray.

Lo! thro’ the gloomy night, with angry blaze,

Trails the fierce Comet, and alarms the Stars;

Each waning Orb withdraws its glancing rays,

Save the red Planet, that delights in wars.

Then, with broad eyes upturn’d, and starting hair,

Gaze the astonish’d Crowd upon its vengeful glare.

Gleams the wan Morn, and thro’ LLANGOLLEN’S Vale

Sees the proud Armies streaming o’er her meads.

Her frighted Echos warning sounds assail,

Loud, in the rattling cars, the neighing steeds;

The doubling drums, the trumpet’s piercing breath,

And all the ensigns dread of havoc, wounds, and death.

High on a hill as shrinking CAMBRIA stood,

And watch’d the onset of th’ unequal fray,

She saw her Deva, stain’d with warrior-blood,

Lave the pale rocks, and wind its fateful way

Thro’ meads, and glens, and wild woods, echoing far

The din of clashing arms, and furious shout of war.

From rock to rock, with loud acclaim, she sprung,

While from her CHIEF the routed Legions fled;

Saw Deva roll their slaughter’d heaps among,

The check’d waves eddying round the ghastly dead;

Saw, in that hour, her own LLANGOLLEN claim

Thermopylae’s bright wreath, and aye-enduring fame.

Thus, consecrate to GLORY. — Then arose

A milder lustre in its blooming maze;

Thro’ the green glens, where lucid Deva flows,

Rapt Cambria listens with enthusiast gaze,

While more enchanting sounds her ear assail,

Than thrill’d on Sorga’s bank, the Love-devoted Vale.

‘Mid the gay towers on steep Din’s Branna’s cone,

Her HOEL’S breast the fair MIFANWY fires.—

O! Harp of Cambria, never hast thou known

Notes more mellifluent floating o’er the wires,

Than when thy Bard this brighter Laura sung,

And with his ill-starr’d love LLANGOLLEN’S echoes rung.

Tho’ Genius, Love, and Truth inspire the strains,

Thro’ Hoel’s veins tho’ blood illustrious flows,

Hard as th’ Eglwyseg rocks her heart remains,

Her smile a sun-beam playing on their snows;

And nought avails the Poet’s warbled claim,

But, by his well-sung woes, to purchase deathless fame.

Thus consecrate to LOVE, in ages flown,—

Long ages fled Din’s-Branna’s ruins show,

Bleak as they stand upon their steepy cone,

The crown and contrast of the VALE below,

That, screen’d by mural rocks, with pride displays

Beauty’s romantic pomp in every sylvan maze.

Now with a vestal lustre glows the VALE,

Thine, sacred FRIENDSHIP, permanent as pure;

In vain the stern Authorities assail,

In vain Persuasion spreads her silken lure,

High-born, and high-endow’d, the peerless Twain,

Pant for coy Nature’s charms ‘mid silent dale, and plain.

Thro’ ELEANORA, and her ZARA’S mind,

Early tho’genius, taste, and fancy flow’d,

Tho’ all the graceful Arts their powers combin’d,

And her last polish brilliant Life bestow’d,

The lavish Promiser, in Youth’s soft morn,

Pride, Pomp, and Love, her friends, the sweet Enthusiasts scorn.

Then rose the Fairy Palace of the Vale,

Then bloom’d around it the Arcadian bowers;

Screen’d from the storms of Winter, cold and pale,

Screen’d from the fervours of the sultry hours,

Circling the lawny crescent, soon they rose,

To letter’d ease devote, and Friendship’s blest repose.

Smiling they rose beneath the plastic hand

Of Energy, and Taste; — nor only they,

Obedient Science hears the mild command,

Brings every gift that speeds the tardy day,

Whate’er the pencil sheds in vivid hues,

Th’ historic tome reveals, or sings the raptured Muse.

How sweet to enter, at the twilight grey,

The dear, minute Lyceum of the Dome,

When, thro’ the colour’d crystal, glares the ray,

Sanguine and solemn ‘mid the gathering gloom,

While glow-worm lamps diffuse a pale, green light,

Such as in mossy lanes illume the starless night.

Then the coy Scene, by deep’ning veils o’erdrawn,

In shadowy elegance seems lovelier still;

Tall shrubs, that skirt the semi-lunar lawn,

Dark woods, that curtain the opposing hill;

While o’er their brows the bare cliff faintly gleams,

And, from its paly edge, the evening-diamond streams.

What strains Aeolian thrill the dusk expanse,

As rising gales with gentle murmurs play,

Wake the loud chords, or every sense intrance,

While in subsiding winds they sink away!

Like distant choirs, “when pealing organs blow,”

And melting voices blend, majestically slow.

“But ah! what hand can touch the strings so fine,

Who up the lofty diapason roll

Such sweet, such sad, such solemn airs divine,

Then let them down again into the soul!”

The prouder sex as soon, with virtue calm,

Might win from this bright Pair pure Friendship’s spotless palm.

What boasts Tradition, what th’ historic Theme,

Stands it in all their chronicles confest

Where the soul’s glory shines with clearer beam,

Than in our sea-zon’d bulwark of the West,

When, in this Cambrian Valley, Virtue shows

Where, in her own soft sex, its steadiest lustre glows?

Say, ivied VALLE CRUCIS, time-decay’d,

Dim on the brink of Deva’s wandering floods,

Your riv’d arch glimmering thro’ the tangled glade,

Your grey hills towering o’er your night of woods,

Deep in the Vale’s recesses as you stand,

And, desolately great, the rising sigh command,

Say, lonely, ruin’d Pile, when former years

Saw your pale Train at midnight altars bow;

Saw SUPERSTITION frown upon the tears

That mourn’d the rash irrevocable vow,

Wore one young lip gay ELEANORA’S smile?

Did ZARA’S look serene one tedious hour beguile?

For your sad Sons, nor Science wak’d her powers;

Nor e’er did Art her lively spells display;

But the grim IDOL vainly lash’d the hours

That dragg’d the mute, and melancholy day;

Dropt her dark cowl on each devoted head,

That o’er the breathing Corse a pall eternal spread.

This gentle Pair no glooms of thought infest,

Nor Bigotry, nor Envy’s sullen gleam

Shed withering influence on the effort blest,

Which most should win the other’s dear esteem,

By added knowledge, by endowment high,

By Charity’s warm boon, and Pity’s soothing sigh.

Then how should Summer-day or Winter-night,

Seem long to them who thus can wing their hours!

O! ne’er may Pain, or Sorrow’s cruel blight,

Breathe the dark mildew thro’ these lovely bowers,

But lengthen’d Life subside in soft decay,

Illum’d by rising Hope, and Faith’s pervading ray.

May one kind ice-bolt, from the mortal stores,

Arrest each vital current as it flows,

That no sad course of desolated hours

Here vainly nurse the unsubsiding woes!

While all who honour Virtue, gently mourn

LLANGOLLEN’S VANISHED PAIR, and wreath their sacred urn.