Re-posted from Archaeodeath

Ad Gefrin/Yeavering is one of the most famous of archaeological sites from early medieval Britain. This is not simply because of the nature of the archaeology uncovered, but also the way it was explored and the interpretations made about it.

The Battle Stone and Yeavering Bell

Excavations at this site directed by Brian Hope-Taylor revealed evidence for a multi-phased, short-lived royal Anglo-Saxon settlement that straddled the period of Christian conversion from the late sixth to late seventh centuries AD.

Yet Ad Gefrin‘s story is not static, it is ever-changing. The site remains a focus of intensive interest, debate and reinterpretation, and perhaps soon new field work.

The management of the site of Ad Gefrin is thanks to the Ad Gefrin Trust’s partnership with Defra and others to ensure access and management to the site

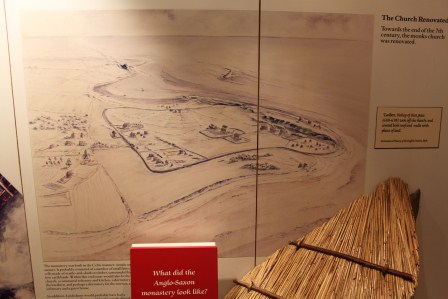

From Hope-Taylor’s and subsequent excavations and survey, we understand Yeavering as a settlement or ‘township’ with evidence of careful planning and alignments around earlier prehistoric features, a sequence of monumental hall buildings and ancillary structures, evidence of metalworking, a possible pagan temple, a ‘theatre’ structure and the Great Enclosure used as either a fort and/or a corral. The site was a focus for burial and ritual activity: early burials focused on prehistoric monuments and later a wooden church because a focus of multiple phases of burial.

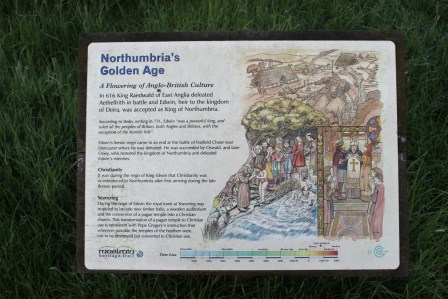

The introductory heritage signboard with artist’s reconstruction by Kelvin Wilson

The way the site was dug was innovative. Chasing high-quality aerial photographs, the excavations were not keyhole, but opened up large areas to reveal and understand the complex sequence of timber buildings surviving only as post-holes and trench-slots. Artefact poor but feature-rich, this was challenging archaeology for the 1950s.

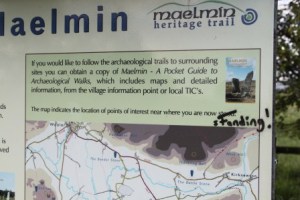

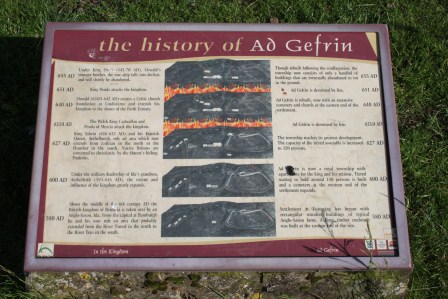

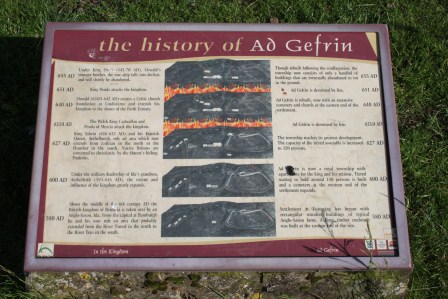

A brave attempt to communicate the complex sequence of archaeology with historical events known from the early history of the kingdom of Northumbria

Gate-post carved with a bird-headdress wearing and four-spear-wielding warrior, with Yeavering Bell in background

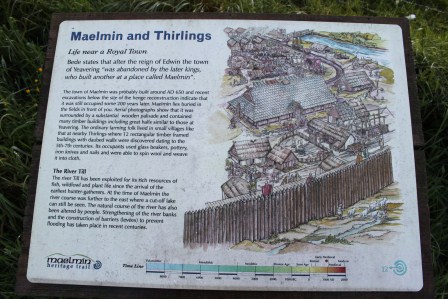

The site is important for its interpretations. Paired with Sutton Hoo, Yeavering has sat as pivotal in interpretations of early medieval kingship and Christian conversion, appearing again and again as a type-site for discussions of the history and archaeology of early Northumbria, the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms more widely, as well as in broader studies of early medieval Britain and North-West Europe. This role comes not only from the quality of the archaeological excavations, but the historical tie-in the site offers. Hope-Taylor connected phases of the settlement’s relatively short evolution to the historical account of the Venerable Bede, linking phases of the site to the succession of pagan and early Christian rulers known from the historical record and phases of destruction to the attacks of Northumbria’s southern rival: Mercia. Moreover, this was the site where Bede informs us that the priest Paulinus, on instruction from Northumbria’s first Christian king, Edwin, baptised the people of Bernicia in the River Glen.

Ad Gefrin – the Hill of Goats – is evoked here in the gate-post that simultaneously marks the site and throws the eye up to the hill-fort of Yeavering Bell behind

The power of the site has not been restricted to this historical narrative, however. The archaeology itself has spawned new narratives regarding the inheritance of the British past – the dominating hill-fort of Yeavering Bell, the reuse of a prehistoric burial mound, henge monument and postulated stone circle and the functions of elite settlements in the early Middle Ages. The halls themselves, the assembly structure and so much else have taken on narrative lives of their own within the academic and population literature.

Yet, this site is only partially understood and this is often forgotten in the popular accounts and many striking artist’s reconstructions afforded to the site.

The other introductory signboard, showing the aerial photograph that inspired Hope-Taylor’s excavations, and the great man himself.

Only a sample of the site was investigated by Hope-Taylor and there are a series of festering frustrations among archaeologists regarding the chronological sequence he revealed and the nature of his interpretations. Excavations in the 1970s revealed more of the site and its later prehistoric origins as a ceremonial complex. More recently, geophysics has been conducted on the site and more features identified. And yet there remains a need to ask fresh questions of the site and possibly conduct new fieldwork in and around this important location.

The empty field that was once Ad Gefrin, with Yeavering Bell

From a heritage perspective, the site is all about absence. There is literally nothing to see in reality. The historical narrative is for the imagination. Likewise, there is nothing to see about the ground surface and no heritage reconstructions have been attempted. It is just a field.

The western access to the site from the road

Only recently, through the efforts of the Ad Gefrin Trust, have attempts been made to present this important site to visitors. Developments have included the addition of a lay-by and monument, a pathway and new access gates for disabled and able visitors, a minimal number of well-constructed signboards, wonderful evocative carved gateposts inspired by the site’s history and Hope-Taylor’s own artwork. There is a management plan to retain the area of the excavations under grass rather than cultivation.

Access to the site via hinged kissing gates

The visitor is still left to face an empty field. Perhaps this is the correct way to leave the site. It is an experience that is largely and effectively ‘virtual’ experience in two senses. First, there is plenty of information online. The virtual is what the physical site is all about too. You are forced to engage with absence and how the topography implies this absence. Rather than through audio-wands and gift-shops and a panoply of sign boards, you are left to wander the field, imagining the phases of timber buildings that once populated this open space. You can also walk up Yeavering Bell and view the site en route, imagining the relationship between this striking hill, its hill-fort, and the Anglo-Saxon royal palace in its shadow.

Goat

Recently, I was invited to contribute to a research workshop organised by the Ad Gefrin Trust at Northumberland County Council’s offices. A brave thing to do to get regional and national ‘experts’ to comment on a draft proposal for new research at and around the site of Yeavering. Everyone has opinions about sites like this, and there was frank disagreements about the way to go forward. Indeed, this was the aim: to get some different views on what could/should be done, and what could/should not be done at this site.

I felt particularly guilty that I was being asked for an ‘expert’ opinion when I had never visited the site. I was relieved to meet others who had only just visited, or had not visited the site at the meeting. Anyway, I rectified that by visiting myself the following morning en route to Bamburgh and Lindisfarne.

View northwards over the site of Ad Gefrin

My impressions were many and striking. The site is ‘dramatic’ in no uncertain terms, not because the site’s immediate topography is particularly marked, in some ways it is quite subtle to the immediate impression. This is no Dunadd or Bamburgh. However, it is the combination of factors that the site ‘connects’ to that are important. The whaleback ridge upon which the Anglo-Saxon site was situated was close to the river and close to the northern edge of the Cheviot Hills and the massive hill of Yeavering Bell encircled by ancient earthworks. Perhaps more important still were the more subtle features in the immediate vicinity that also captured my imagination in relation to the known archaeology and also to areas that I don’t believe have received archaeological interventions. The isolated and enigmatic ‘Battle Stone’ nearby, the other spurs along the edge of the River Glen’s flood plain and the wider space between Yeavering Bell and the Ad Gefrin site all cry out for further attention, as do the smaller defended enclosures on nearby hills. I also noticed how the road, layby and managed ‘site’ gives a false impression to the extent and character of the potential Anglo-Saxon settlement. It is likely that Hope-Taylor opened and explored only a tiny fraction, perhaps an elite focus, of a far wider settlement, that in itself, sat within a local context in relation to a series of other settlements.

More Anglo-Saxon carving

In short, as a fresh visitor to a site that I have long been familiar with from an archaeological perspective, the power of place in understanding, writing, and visualising Yeavering came home to be very strongly. Yet equally, I understood clearer than before why archaeologists remain intrigued and frustrated by what we think we know about this most iconic and distinctive of early medieval settlements.

The lay-by, monument and heritage signboard, plus University of Chester fleet vehicle

The monument at the Ad Gefrin site

As part of the Past in its Place project, I have a vision to write about Yeavering, not with regard to the early medieval settlement alone, but because Yeavering is a classic site for debating ‘the past in the past’, the inheritance of the prehistoric past in the Anglo-Saxon period, but also the subsequent literary, historical and archaeological reception of this iconic site where Christianity was brought to the kingdom of Bernicia that once straddled area that was to become the English-Scottish border