Bamburgh Castle from the beach

I recently visited Bamburgh where I received a warm welcome from Bamburgh Research Project director Graeme Young and his team. I was last at Bamburgh as a child. From photographs and from memory, I recall the castle as dramatic indeed. I half-expected to be underwhelmed by the reality. However, the site, its archaeology and its landscape failed to disappoint. A spectacular location and a fantastic archaeological site. What is ‘Bamburgh’ in archaeological terms? Well, I regard it as a famous multi-period fortress: the focus of the long-running but perhaps still under-valued archaeological research project: the Bamburgh Research Project (BRP).

BRP excavations in Bamburgh Castle, chasing Hope-Taylor…. in the rooms behind, sealed like a mummy’s tomb, BRP uncovered Hope-Taylor’s work room!

Excavations by BRP have revealed trench-slots possibly related to a guard-room and gate for the Anglo-Saxon fortress.

Their ongoing mission is to boldly go where others have gone before. Incorporating many training and community dimensions, their recent work has involved the re-evaluation early antiquarian discoveries and re-exploring the archives and trenches opened by Brian Hope-Taylor (of Yeavering fame) who dug at the castle but failed to complete or publish his work. Their other ongoing mission – that rubs shoulders (and trenches) with the first – is to boldly go where no-one has been before, since BRP has produced many exciting new discoveries both outside the castle and inside the castle grounds (in the trenches formerly opened by Hope-Taylor and beyond in new areas).

BRP’s excavations of the Bowl Hole early medieval cemetery have provided exciting new evidence of the complex social groups contributing to an Anglo-Saxon royal fortress’s population.

Meanwhile their work within the castle is providing evidence both in the area of castle’s church where they may have found an early medieval crypt, and in two zones in the northern half of the castle near what may have been the early medieval entrance and industrial areas serving the Anglo-Saxon fortress.

The likely original approach to the fortress from the west-north-west.

In very broad and simple terms, BRP are revealing new information about the socio-political and industrial dimensions of the fortress, as well as its mortuary and religious significance. Despite the inevitable restrictions on working at an open heritage attraction overlain by centuries of monumental late- and post-medieval castle architecture, BRP have soundly dismissed any cynic who might think that digging in a castle will only reveal slight traces of early medieval activity. If this wasn’t enough, reinterpreting other archaeologist’s old trenches is challenge enough but in the context of complex layers and a shallow bedrock, it is even more challenging. Unsurprisingly, for almost a decade, I have supported students from Exeter and Chester wishing to go on their fieldwork at Bamburgh but it was great to see the site finally in person.

I defer to their own website and blog for details regarding the archaeology and you can read about some of their recent discoveries in the castle’s museum, a book composed for visitors about the site’s archaeology, and also in academic publications in journals like Medieval Archaeology and Archaeologia Aeliana.

A classic and effective presentation strategy, an early medieval comb displayed next to a replica

Display of a hoard of copper coins of Middle Anglo-Saxon (mid-ninth century) date, found in the excavations by BRP.

Early Medieval Bamburgh

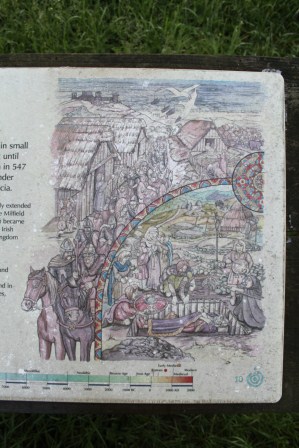

‘The city of Bebba’. As an early medievalist, the task is to see past all of the later medieval rubbish, and post-medieval fantasies regarding the Middle Ages, to try to discern what physical evidence survives from the Anglo-Saxon phase. For this was an Anglo-Saxon fortress. As such, it is best seen as one example of the many early medieval uses for hill-top fortifications. Hence it is best described as a ‘hill-fort’ in my view, prior to its recreation as a medieval castle.

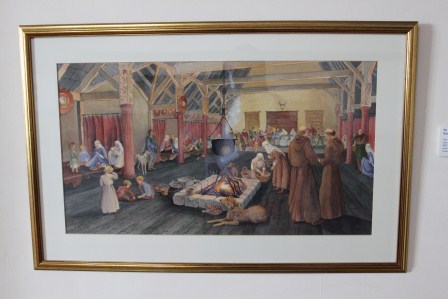

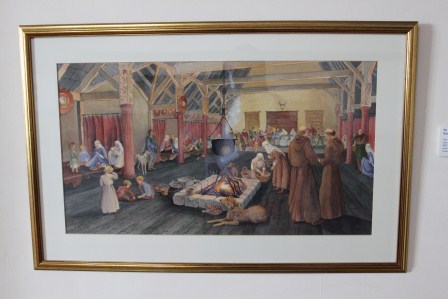

Jayne Brain’s reconstruction of a royal hall of Anglo-Saxon date.

Indeed, it is utterly anachronistic to see its early medieval phases as a ‘castle’, although I concede that the presence of later phases, and the place-name, make such back-projections seductive and confusing for visitors and experts alike. I still find it amazing that early medieval hill-forts are frequently caricatured as settlements of the ‘Britons’ and ‘Picts’ when there is plenty of evidence for their use in lowland Britain – in areas that are generally regarded as ‘Anglo-Saxon’, during the fifth to eleventh centuries AD. Bamburgh is one such example.

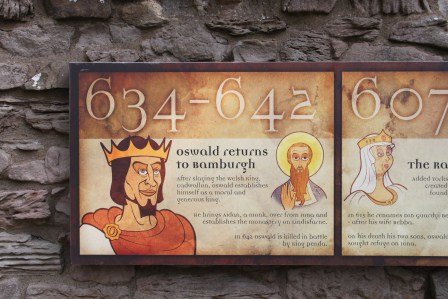

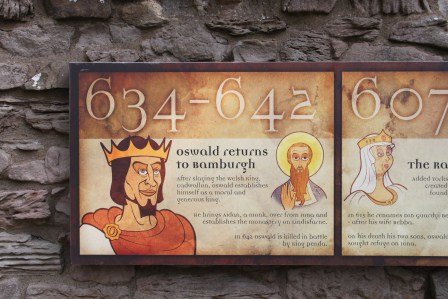

Oswald almost certainly didn’t look like this, but that isn’t a problem in itself.

Re-posted from Archaeodeath

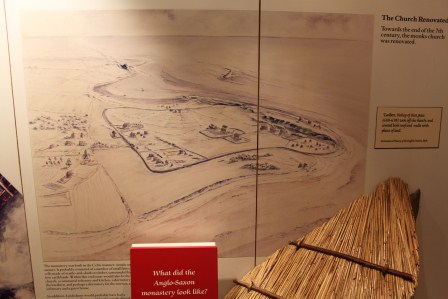

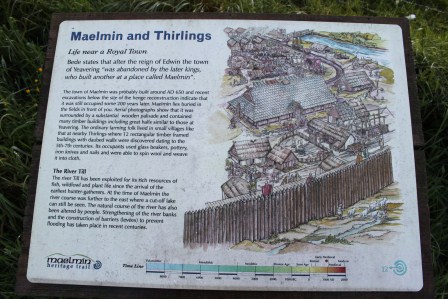

BRP believe they have found traces of a box-rampart in the northern area of the citadel. Analogy with Yeavering leads to imaginative but likely reconstructions of the monumental timber hall (or halls) that would have formed the focus of the royal site on the highest part of the hill-top, paired with one or more churches and chapels further to the east underlying the later church of St Peter.

The ruined church, where BRP believe was a crypt containing the relics of St Oswald

Did the Norman keep overlay a pre-existing palace site of the Earls of Northumbria?

A Place of Memory?

As an archaeologist of memory, the complex genealogy of the site, its enduring use and reuse as a place of power, make it of interest in a contrasting sense. From this perspective, my interest is not to strip away later activity, but to consider how the site’s ‘pedigree’ has been augmented and rewritten in multiple ways within the Early Middle Ages and then subsequently from the Anglo-Saxon period to the present day through a near-continuous sequence. Approaching Bamburgh’s long history of occupations means more than charting a time-line of events. It is instead about considering how the history of the site has fed into its social memories in contrasting and varied ways over time; how the site has been packaged and repackaged, subsumed and highlighted in contrasting ways. This is an interesting and legitimate focus of archaeological research in itself.

Hope-Taylor found evidence of Iron Age activity. It would be interesting to learn how much prehistory can be discerned and whether there was a demonstrable Iron Age/Roman predecessor to the early medieval fortress. How precisely was the early origin of the castle important in subsequent periods of use and reuse? These questions still seem to have sketchy answers at present, but the ongoing research by BRP is revealing more and more information about the long-term use of the site and its adaptations, but also its continuities over time. In many ways this is the inverse of the situation at Yeavering/Ad Gefin, where the argument for a ‘forgetting’ of the site after the seventh century still remains plausible.

Bamburgh castle, view from the south-west

Landscape Archaeology

As a landscape archaeologist, one would take a further view, noting not only its maritime situation but its maritime context, the near presence of the Farne Islands, the monastery of Lindisfarne, and its situation on the maritime highway that defined the kingdom of Northumbria from the Firth of Forth to the Humber. A landward perspective is also legitimate, including the relationship to the dunes in which an early medieval cemetery has received extensive excavation by the Bamburgh Research Project, to the church of St Peter and the settlement of Bamburgh as well as the wider hinterland of land use. In many ways, Bamburgh is a node in a complex multi-scalar early medieval landscape of power and faith.

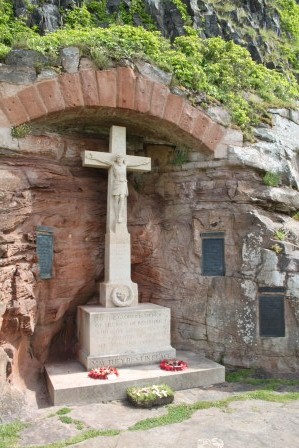

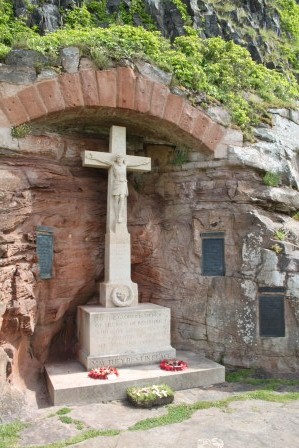

The war memorial, set into the rock at the base of Bamburgh Castle

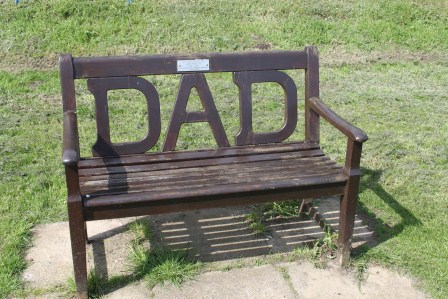

A memorial bench with a view of the castle

Memorial within the ruined church to the first Lord Armstrong

Contemporary Commemoration

I was interested in how recent commemorative memorials to individuals and groups modern and medieval were integrated into the castle and its environs, including the industrialist and inventor, the first Lord Armstrong, who has a museum and plaques dedicated to his memory, while St Oswald is commemorated in the ruins of the chapel when his relics may once have resided. There is even a plaque commemorating the castle as a film-set, as for the 1972 film Macbeth. Equally fascinating was the utilisation of the castle’s immediate context as a memorial environment including Bamburgh’s First and Second World War memorial, and the commemoration of the cult of Victorian heroine Grace Darling, involving memorials in the church, churchyard and her RNLI museum.

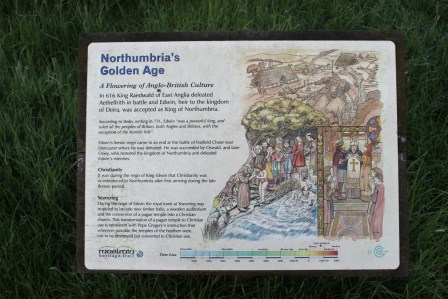

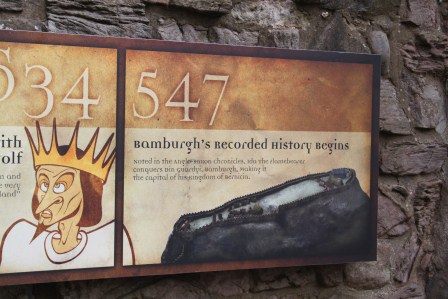

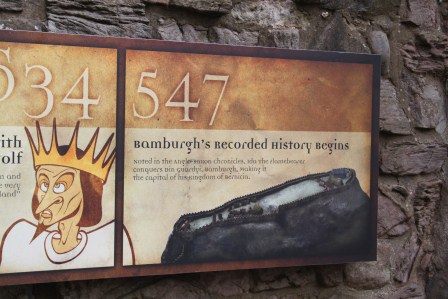

The start of the Bamburgh time-line…. I love the depiction of Aethelfrith

The archaeology museum

The Bamburgh chair, based on designs by Joanne Kirton

Tourists posing for pics in the Bamburgh chair

Heritage and Memory

From a heritage perspective, it is of interest in many regards as a privately owned site (i.e. not under the guardianship of English Heritage or the National Trust). What struck me was how archaeologists have been permitted to work in the heritage site conducting long-term excavations but also how much their work has been incorporated into the heritage signboards, reconstructions and even an archaeological museum within the castle. I was particularly proud of my student – Joanne Kirton’s – design utilised in the reconstruction of the ‘Bamburgh throne’, now a popular option for photographs by tourists. There are very few places where you can ‘sit like an Anglo-Saxon’…

Gate forged with the initials ‘B H T’ (Brian Hope-Taylor)

Commemorating Archaeology

Interestingly, there is a striking piece of material culture commemorating the failed excavations of Brian Hope-Taylor – gates to his dig forged with his initials! I want some of these on my future excavations….

Summary

So from my perspective, Bamburgh is important as an early medieval site, as a place of memory and power over the long term, as a node in a complex maritime landscape. Bamburgh is also an active and distinctive heritage site with everything from cheesy torture chambers to ongoing excavations to view.