Yeavering Bell from the south

Re-posted from Archaeodeath

At the research workshop on new research at Ad Gefrin/Yeavering, many of the experts present proclaimed, from different perspectives, that you cannot understand Ad Gefrin without understanding the hill-fort of Yeavering Bell. Ad Gefrin, it was said, is ‘in the shadow’ of Yeavering Bell. This was no empty metaphor: during a large portion of the year, the Ad Gefrin site is in the shadow of the hill over which the low winter sun cannot project. Frosts stay longest at the Ad Gefrin site than in surrounding fields I was told.

And indeed, to observe Ad Gefrin and understand its situation I was told that one cannot do better than to ascend Yeavering Bell. Many of those there told me they had made out possible crop-marks from the perspective offered by the hill upon which the fort is situated.

Stream on the ascent

View over the Ad Gefrin site during the ascent of Yeavering Bell

Yeavering Bell is the only ‘true’ hill-fort in the Cheviots although it must be said that almost every hill along the northern edge of the Cheviots has a smaller fortification of presumed (if not proven) late prehistoric date upon it. Aerial photograph has shown how this is simply a surviving dimension of a wider settlement pattern; in lower areas similar fortified sites have been obliterated by medieval and post-medieval agriculture. Despite this advance in knowledge, Yeavering Bell still stands out in terms of the prominence of the hill itself and the size of the defences and the number of house-platforms identified within it.

Leading the way

There remains considerable debate regarding Yeavering Bell’s date of construction and occupation and whether the small hill-top fortification within the hill-fort, around the highest point is a contemporary Anglian fortification linked to the palace site of Ad Gefrin. Surveys and excavations have only partly identified the extent to which this site may offer ‘continuity’ from the first millennium BC through to the mid/later first millennium AD. Was Ad Gefrin a direct successor to a persistent central (and possibly sacred) place? Or was it a reactivation of a locale whose original (or many previous) uses were long forgotten but whose monumental and topographical supremacy could never to be ignored?

Up Yeavering Bell

I won’t use this blog as the place to wade into these debates yet, and you can read the views of the different authors in Paul Frodsham and Colm O’Brien’s fascinating survey Yeavering: People, Power and Place. Richard Bradley’s superb 1987 paper in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association, that has done so much to inspire me and others in thinking about ‘the past in the past’, should also never been ‘forgotten’. Before that, Hope-Taylor’s publication on Yeavering has many (if sometimes very frustratingly vague) things to say about the hill-fort. For a list of available publications, see the Gefrin Trust website. Roger Miket has recently published on this topic in Archaeologia Aeliana but I have yet to secure a copy of this publication.

Farm building and field walls: post-medieval

What I will say is that I often rant against archaeologists who define sites by period, when those sites persisted and were open to reinterpretation and reuse long after their initial construction. Equally though, I am cynical of claims at ‘continuity’ without precise clarification regarding what is meant by this.

View south from Yeavering Bell over the ramparts

I intend to synthesise an appraisal of the hill-fort and its relationship with Ad Gefrin with regard to its remembering and its forgetting, responding to the work of Bradley, Frodsham, Oswald and others, as part of the Past in its Place project.

The summit cairn of Yeavering Bell

In doing so, my aspiration is to try and disagree with everyone, not because I think that everyone who has worked on this fascinating site and its context is ‘wrong’, but because I feel their frames of reference and theoretical perspectives (where expressed) are different from mine and my colleagues with our interest in the history of memory from archaeological and literary perspectives.

Me at the summit of Yeavering Bell

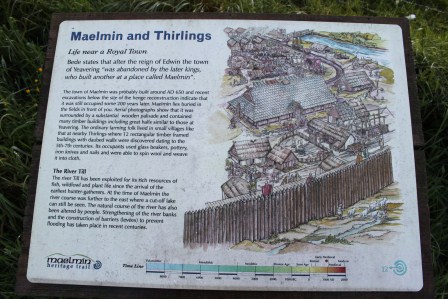

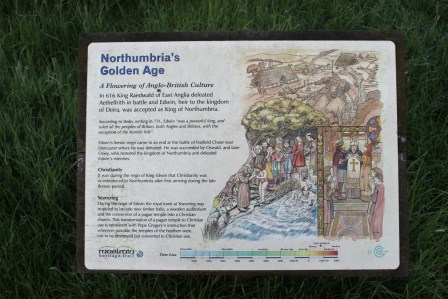

So on the day after I visited Ad Gefrin and Bamburgh, followed by a visit to Lindisfarne in heavy rain, I went back to park at the Ad Gefrin lay-by and walked up Yeavering Bell on a windy but beautifully warm and sunny summer’s morning. I was up early, having been awoken by Berwick-upon-Tweed drunks at 4 am (my Travelodge was adjacent to a 24-hour McDonald’s restaurant that clearly attracts the intoxicated and inarticulate of Berwick on the Sunday morning after a Saturday night). I stopped en route at Maelmin (topic of another blog inevitably) before I moved on to ascend Yeavering Bell.

The summit of Yeavering Bell with the line of the fortlet’s defences running around the summit.

From the perspective of the Past in its Place project, visiting the site was a real eye-opener as expected and promised. I saw much that I anticipated but far more than I didn’t. Visiting Ad Gefrin was simply not enough.

View over the Ad Gefrin site from Yeavering Bell

What an experience! Alone on a Sunday morning, and with only semi-inquisitive sheep, a whimbrel (symbol of Northumberland National Park) and a skylark for company, I got to ascend, explore and descend a fabulous hill-fort.

The site affords stupendous views southwards over the Cheviots and north over the valleys of the rivers Glen, Till and Tweed. I saw no goats, I am sad to say but I saw the fortifications, the fortlet at the highest point, and some of the house platforms.

I can also attest that the Ad Gefrin site is intimately bound up visually and physically with the hill-fort, but I am not convinced it was bound up with the hill-fort in any practical or successive sense. It seems to me that the hill and the earthworks would have significance in the early medieval period even if the active use of the hill-fort was restricted to a short duration within the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age. There may be traces of Roman activity on the hill-top, but its scale and looming presence would surely be enough to afford the site significance for the emerging kingdom of Northumbria in the late sixth and early seventh century.

With these thoughts in mind, I aim to return in August with the group of Past-in-its-Placers to outline and refine my musings.

The hill-fort defences